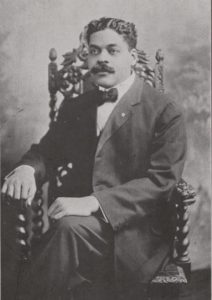

Meet Arturo Alfonso Schomburg

By Dr. Byrum Patrick

Arturo (Arthur) Schomburg (1874-1938) was born in 1874 in Santurce (now part of San Juan), Puerto Rico. His father was a businessman whose mother was from India and whose father was of German stock. Arturo’s mother, a midwife, was originally from St. Croix in the Virgin Islands and was of African descent.

Arturo (Arthur) Schomburg (1874-1938) was born in 1874 in Santurce (now part of San Juan), Puerto Rico. His father was a businessman whose mother was from India and whose father was of German stock. Arturo’s mother, a midwife, was originally from St. Croix in the Virgin Islands and was of African descent.

As a child he would read to workers rolling cigars in a factory to help them pass the time. He developed a keen interest in the novels, news reports and political discussions that he would read to them. When he was in the fifth grade, his teacher told him that blacks had no history, heroes, or accomplishments. This only proved to be a challenge to him and from this moment on he vowed to “track like a bloodhound” to find the lost history of Africans, both on their own continent and in the diaspora.

He was educated in commercial printing in Puerto Rico and then studied Negro literature at St.

Thomas College in Danish ruled Virgin Islands. With letters of recommendations from the

tobacco businessmen and the owner of a print shop where he had worked, at age 17 he moved

to the Harlem section of New York. While continuing to study African and Afro-American

history, he eventually taught Spanish, worked as a messenger for a legal firm, and later became

supervisor of the messaging department of Bankers Trust Company.

During this time, Arturo became very involved in the independence movements for Cuba and

Puerto Rico (from Spain) and co-founded Los dos Antillas dedicated to this purpose. When the

islands became possessions of the United States after the Spanish-American War in 1898, these

groups dissolved.

In the United States Arturo, who called himself Afro-Puerto Rican, found that he was not

initially accepted by American blacks, who to this point did not have a lot of experience with

Latino immigrants. At the same time he experienced the white racism that they were suffering

under, too.

He decided to ignore the differences and to concentrate on the global history that they both

shared. He began what became extensive research on this subject, collecting documents,

getting oral histories, and writing scholarly articles himself. His first published article was “Is

Hayti Decadent?” in 1904. In 1909 he published Placido, A Cuban Martyr, a short pamphlet

about a Cuban poet and independence fighter.

Arturo believed that through education and learning their history, African-Americans would be

better able to advance socially and economically. He knew that the official history taught was

white-washed and ignored the contributions of those of African descent by not mentioning

them. In 1911 he co-founded, with John Edward Bruce, the Negro Society for Historical

Research, which for the first time brought together African, West Indian and Afro- American

scholars. He joined the exclusive American Negro Academy in 1914 and served as its fifth and

last president from 1920 to 1928. Founded in 1897, its purpose was to refute racist scholarship

and publish the history and sociology of African-American life, while also promoting black

claims to individual, social, and political equality.

Arturo played an important role in the Harlem Renaissance, a flowering of intellectual, political

and artistic movements brought about by the concentration of blacks in Harlem from across the

United States and the Caribbean. This peaked in the 1920s and during this time Schomburg

published his influential and widely distributed essay “The Negro Digs Up His Past”. His

collection of books, manuscripts, slave narratives, artwork and other artifacts eventually

became so massive that it outgrew the space in the apartment that he and his wife shared. In

1926 the Carnegie Corporation purchased it for $10,000 and donated it to the New York Public

Library. The library appointed him the curator of the collection titled the Schomburg Collection

of Negro Literature and Art (later renamed the Arthur Schomburg Center for Research in Black

Culture). Arturo used the money he received to travel to Spain, France, Germany, and England

to seek out more pieces of black history to add to his collection. In the early 1930s, while

serving as Curator of the Negro Collection at Fisk University in Nashville, he traveled to Cuba to

meet with artists and writers and add yet more to his collection.

Schomburg died of complications from dental surgery in 1938. In 2002 scholar Molefi Kete

Asante named him on his list of the 100 Greatest African Americans.